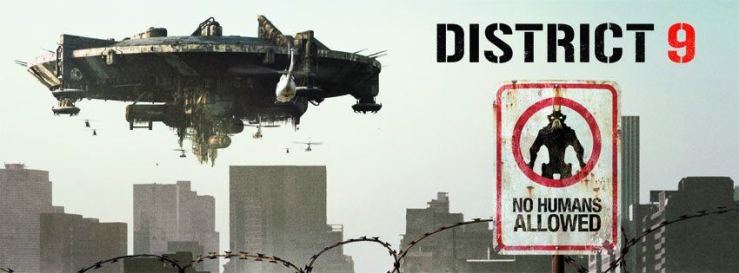

District 9 is a movie about aliens, but it’s a different sort than the usual kind (the Third Kind, if you will). They arrive on Earth, but not as warlike monsters hell-bent on the destruction of the human race, like those in Independence Day. Their discovery has none of the eerie ethos and cerebral diplomacy of Arrival. They are not judges of humanity, or ethereal beings with higher knowledge to offer Earth.

Rather, the aliens come to earth as emigrants, refugees of sorts. They appear over Johannesburg, South Africa, and the government suddenly has 1.8 million sick aliens on its hands, lost and in need of help.

So how does the human race react to a alien refugee crisis?

The “prawns,” as the creatures come to be called, are placed in a makeshift camp that quickly deteriorates into a slum. District 9 becomes a festering ground for dangerous gangs, weapons dealing, crime, filth, and squalor. Riots and fights break out between humans and aliens, and the people of Johannesburg call for the prawns to be evicted farther away from the city. MNU is in charge of the eviction—but they’ve got ulterior motives of utilizing alien weaponry. Wikus van de Merwe, worker for MNU, comes into contact with alien biotechnology as he assists in the evictions. He must run for his life as he himself begins to morph into a prawn, and must find out how to reverse the transformation if he wants to remain a human. It’s on this stage that the story of District 9 takes place.

In terms of visual storytelling style, District 9’s faux-documentary new clips and interviews help ground the film, giving the story a more concrete, realistic feel despite the fictitious subject matter. We watch Wikus as we might watch a star of a survival show on National Geographic. The camera’s presence is intentionally tangible through handheld shots, as though some of the footage were captured spontaneously by on-site news or security cameras. This cinema-verite style complements the gritty tone of the movie.

It’s interesting to note some of the common color palettes in sci-fi movies. Some, like Star Trek or Gravity, are made up of soft blues, greys, and whites, signifying sleek technology and giving the films a clean-cut, modern look. Others, including Blade Runner and the Matrix, contrast dark hues with bright neons. I call this “Cityscape scifi.” District 9 is an example of “grunge sci-fi.” Its palette of muddy greys, browns, greens and blacks give the film an earthy, grimy texture, perfectly matching the dark subject matter and the setting of the film—a squalid South African ghetto.

District 9 is also philosophically and thematically rich. It forces the viewer to ask questions, and brings up a lot of questions that many of us would not like to consider. By placing humans in a situation with non-humans, it throws human nature into a different perspective. District’s 9 is disturbing, unsettling, and brutally frank in its depiction of the worst sides of humanity. It’s not a story of the triumph of human nature over alien destruction. Rather, it’s a brutal portrait of depravity, the worst sides of human nature—selfishness, prejudice, greed, and distrust. What’s perhaps most disturbing is that, if the events in the film were to actually take place, the grim outcomes shown in the film—xenophobia, genocide, and unethical experimentation—would be quite likely. Mankind has a record of painting those who are different from the majority as animals, “others” to be feared and avoided. This has happened throughout history. Director Neill Blomkamp, who was born in Joberg, created the world of Dictrict 9 as an allegory for an almost identical situation in apartheid South Africa. However, the picture he painted in District 9 is also relevant with regards to European and American treatment of indigenous people and minor ethnicities, as well as for modern-day events such as the refugee crisis going on in Europe today.

At the beginning of the film, as tensions between prawns and humans escalate, one boy tells the news camera, “If they were from another country, we might understand, but they are not from this planet at all.” The fact is, we wouldn’t. And we haven’t. District 9 makes this issue painfully apparent.

It also masterfully combines this sociopolitical commentary with great filmmaking. One writer aptly put it:

“For all of its attention to historical echoes, District 9 is not simply an allegory about forced removals, and the aliens in the movie are not black South Africans in disguise. Rather, what is happening here is something altogether more significant and ambitious: the metaphors and tropes of science fiction are being used to engage rather more deeply and disconcertingly with the nature of racism itself – with the way that racist ideology and discourse deals with the feared, hated, despised (and desired!) ‘Other.’”

This, I believe, was one of the most resonant chords in the whole movie. It’s part what makes it such an genius, incredible piece of cinema. The movie’s sci-fi platform makes its underlying themes more powerful than if it were simply a social doc. By housing a very serious, very real message in a fantastical, unreal setting, Neil Blomkamp gives his film unique impact and meaning.

District 9 is good sci-fi because it is able to use a story about aliens, futuristic weaponry, and interspecies warfare to challenge our own beliefs, philosophies, and prejudices. The best examples of sci-fi in cinema turn our gaze outwards into the far reaches of the stars, imagine the wildest limits of technology and science, but also enable us to examine our innermost selves. It’s good sci-fi because it makes us wonder what’s out there, and at the same time, ponder what we are.

<><><><><><><><><><><>

References

If you’re at all interested in reading more about the politics, philosophy, and cinematic artistry of District 9, please check this article out. It’s incredible.

Becoming the Alien: Apartheid, Racism, and District 9. https://asubtleknife.wordpress.com/2009/09/04/science-fiction-in-the-ghetto-loving-the-alien/